GP fees explained: How your doctor sets their prices

General practitioners (GPs) can set their own patient fees in New Zealand — and they must weigh up several factors when it comes to the cost of their services.

While children under 14 are eligible for free health checks, and cheaper GP visits are available to certain groups through a High Use Health Card or a Community Services Card, everyone else is generally forking out a co-payment to visit their doctor.

So, how do GPs and medical centres decide on those fees? And why do they differ depending on where you are in New Zealand?

First, the government funding

========================

GPs get lower than expected funding boost from Health NZ

There are warnings it could mean some practices shut down, Cushla Norman reports.

GPs receive government funding through a system known as capitation.

Under capitation, GPs get a set amount of money for each enrolled patient they have, each year. They are not paid per visit.

The Government pays this money to Primary Health Organisations (PHOs) who then pay the money down to general practices within that PHO.

Not all patients are funded for the same amount under this system. The funding varies depending on things like a patient's age and gender, said Dr Angus Chambers, a GP and chairman of the General Practice Owners Association of Aotearoa New Zealand (GenPro).

"A very young person will go to the doctor a lot more for a whole lot of reasons and a very old person will too — but a 25-year-old is much less likely to, so there's a lesser [capitation] fee for [them]," he said.

However, this funding system is based around data from more than 20 years ago, Chambers said.

"It's very dated data ... and it's not nearly sophisticated enough," he said. "I get the same payment for a 65-year-old [patient] as I do for a 95-year-old, and a 95-year-old's health needs are exponentially higher than a 65-year-old's," he said.

"[The system] doesn't take into account the age and complexity of people and inequities, so it's generally accepted to be not really that fit for purpose; it's accepted it needs to be changed."

It also doesn't consider that health needs and health care have changed a lot over the past 20 years, Chambers said.

"There's new treatments, new tests, different ways of managing things, a surge in mental health demand — the list goes on."

Deciding on fee increases

=====================

This year's average allowable fee increase is 7.76%.

General practices need to work out how much they need to charge each year to cover costs and keep their business viable.

Underpinning those decisions is a fees review process known as the annual statement of reasonable GP fee increases (ASRFI).

This is a guideline issued by the Ministry of Health. It recommends a maximum percentage GPs can increase their fees by each year, based on predicted cost pressures, such as inflation, labour and other operational expenses.

This year's average allowable fee increase is 7.76%.

GPs can choose to increase their fees by more than the ASRFI, Chambers said, but they are in for a lengthy, expensive process if they do.

"If a practice breaches that ASRFI number, Te Whatu Ora can refer them to the Fees Review Committee," he said.

"[GPs] have to submit data to [the committee]. If they've exceeded [the ASRFI] and the committee thinks it's reasonable, they can go ahead. But if the committee doesn't think it's reasonable, then they can make a recommendation that you reduce your fees.

"There's quite a bit of risk and expense if you exceed the cap [on fee increases]."

Fee variations around the country

===========================

There can be significant variation in how much people pay to see a GP in New Zealand.

The amount people pay to see a GP can vary quite a bit, depending on what part of the country they live in.

Some of this comes down to the actual cost of doing business — leases can be quite a lot higher in Auckland than in small towns, for example — but some of the difference is historic, Chambers said.

He said regions with more socioeconomic deprivation have traditionally charged less because GPs would likely otherwise end up with bad debt and disgruntled patients.

Then, the fees review process and its cap on fee increases locks practices into low fees.

For example, if a GP charged $100 for a patient and was allowed a 5% fees increase, their fee would increase by $5 to $105. A GP in another area charging a $50 co-payment, on the other hand, would only be able to increase their fee by $2.50.

"The gap grows wider and wider because of this policy setting, so practices that have started off [with low fees] get entrenched in this historical discrepancy," Chambers said.

It's leading to what Chambers calls market failure.

"There's not enough GPs, so you're competing more and more [to hire people], and doctors are probably going to higher-paying jobs."

This means some regions, especially rural areas, are at further risk of losing access to general health services.

"We have this workforce shortage, which is partly related to poor policy in terms of training people, but also underfunding, which is making it far more attractive to go into other specialties than general practice."

The knock-on effect

================

Increasing GP fees can mean people put off medical care.

Higher co-payments can mean people put off going to a GP, Chambers said.

"That means they might present later and sicker ... or they can't afford it, so they end up going to the emergency departments and clog [them]."

Chambers said GPs know access to primary care is worse than it's ever been and don't like having to increase fees to cover costs.

But GenPro said last month Te Whatu Ora was failing to cover the increased costs of providing community health care, which ultimately means the cost burden shifts to patients.

PHOs represented by General Practice New Zealand, Te Kāhui Hauora Māori PHOs, and the Hauora Taiwhenua Rural Health Network have all similarly slammed the Government's funding offer for GP services this year.

"[GPs] don't want to increase fees like this because they're part of the community too and their patients are often well known to them — and they feel this is a result of very poor policy for quite a long time from both sides of the political divide," Chambers said.

"We're wearing the stick for failure of the government as a whole.

"[Governments] have had a lot of advice from people telling them that this situation will come around and they've, frankly, ignored it."

Te Whatu Ora told 1News it acknowledges the cost pressures GPs are facing and the growing demand on their services.

"Health NZ-provided services are facing similar pressures in a fiscally constrained environment," Health New Zealand Te Whatu Ora's living well director Martin Hefford said.

"Through our annual capitation uplift offer, we have worked hard to target available funding where it is most needed to support primary health care and general practice."

==========================================

www.1news.co.nz...

=========================================

Poll: As a customer, what do you think about automation?

The Press investigates the growing reliance on your unpaid labour.

Automation (or the “unpaid shift”) is often described as efficient ... but it tends to benefit employers more than consumers.

We want to know: What do you think about automation?

Are you for, or against?

-

9.4% For. Self-service is less frustrating and convenient.

-

43.5% I want to be able to choose.

-

47.1% Against. I want to deal with people.

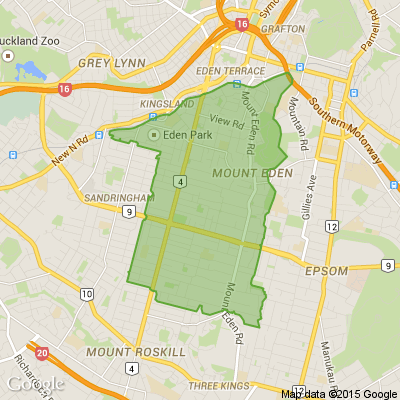

Dry cleaners mt Roskill

Hello our fellow neighbors I was hoping someone would know where the old dry cleaners we had up at the lights on dominion road have moved to?? I was out of town and when I came back they were gone .... I had some items that I would really love to get back but if only I new where they moved to or how to get In Touch with the owners to see what they did with our clothes if they closed down or moved elsewhere? Any updates or news about it would be amazing neighbors. Have a great day

Valentine’s Special | Custom Massage & Energy Healing

A 120-minute bespoke massage and energy-healing session designed to bring awareness and sensation back into the body. Ideal for a grounding, nervous-system reset, and embodied presence.

Valentine’s Special: $200 (120 minutes)

Session includes

- Intuitive, tailored full-body massage

- Integrated energy-healing work

- Premium organic massage oils

- Custom aromatherapy

- 432Hz healing frequency soundscape throughout

Why Valentine’s?

Valentine’s doesn’t have to be outward or performative. This session is a way to reconnect internally, release stored tension, and return to the body with clarity and ease.

About

Experienced professional masseuse and energy healer. Sessions are one-on-one only and adapted precisely to what the body presents on the day.

Available in Helensville, Auckland CBD, or as a mobile service.

Limited Valentine’s availability.

Message to book or enquire.

Loading…

Loading…